Note: This post originally appeared in TechCrunch

Here’s the gist:

- The degree to which a company can utilize habit-forming technologies will increasingly decide which products and services succeed or fail.

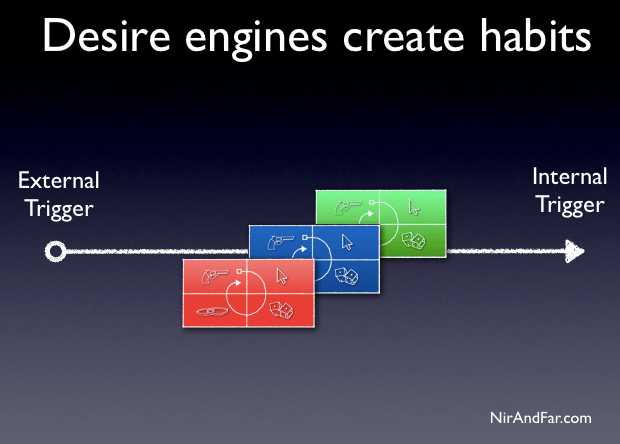

- Addictive technology creates “internal triggers” which cue users without the need for marketing, messaging or any other external stimuli. It becomes a user’s own intrinsic desire.

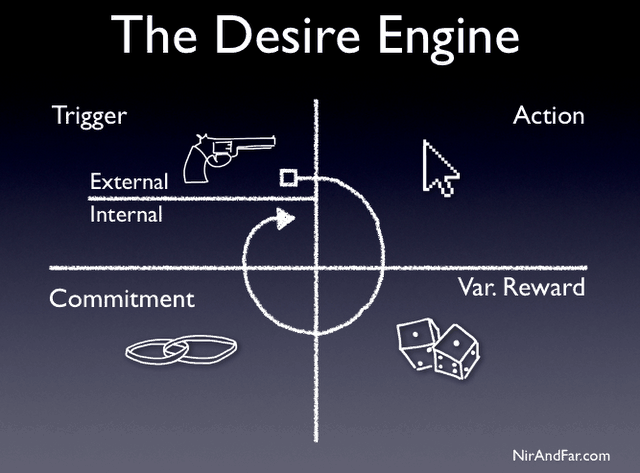

- Creating internal triggers comes from mastering the “desire engine” and its four components: trigger, action, variable reward, and commitment.

- Consumers must understand how addictive technology works to prevent being manipulated while still enjoying the benefits of these innovations.

Type the name of almost any successful consumer web company into your search bar and add the word “addict” after it. Go ahead, I’ll wait. Try “Facebook addict” or “Zynga addict” or even “Pinterest addict” and you’ll soon get a slew of results from hooked users and observers deriding the narcotic-like properties of these web sites. How is it that these companies, producing little more than bits of code displayed on a screen, can seemingly control users’ minds? Why are these sites so addictive and what does their power mean for the future of the web?

We’re on the precipice of a new era of the web. As infinite distractions compete for our attention, companies are learning to master new tactics to stay relevant in users’ minds and lives. Today, just amassing millions of users is no longer good enough. Companies increasingly find that their economic value is a function of the strength of the habits they create. But as some companies are just waking up to this new reality, others are already cashing in.

First-to-Mind Wins

A company that forms strong user habits enjoys several benefits to its bottom line. For one, this type of company creates “internal triggers” in users. That is to say, users come to the site without any external prompting. Instead of relying on expensive marketing or worrying about differentiation, habit-forming companies get users to “self trigger” by attaching their services to the users’ daily routines and emotions. A cemented habit is when users subconsciously think, “I’m bored,” and instantly Facebook comes to mind. They think, “I wonder what’s going on in the world?” and before rationale thought occurs, Twitter is the answer. The first-to-mind solution wins.

Manufacturing Desire

But how do companies create the internal triggers needed to form habits? The answer: they manufacture desire. While fans of Mad Men are familiar with how the ad industry once created consumer desire during Madison Avenue’s golden era, those days are long gone. A multi-screen world, with ad-wary consumers and a lack of ROI metrics, has rendered Don Draper’s big budget brainwashing useless to all but the biggest brands. Instead, startups manufacture desire by guiding users through a series of experiences designed to create habits. I call these experiences “desire engines,” and the more often users run through them, the more likely they are to self-trigger.

I created the desire engine in order to help others understand what is at the heart of habit-forming technology. It highlights common patterns I observed in my career in the video gaming and online advertising industries. While the desire engine is generic enough for a broad explanation of habit formation, I’ll focus on applications in consumer Internet for this post.

Trigger

The trigger is the actuator of a behavior—the spark plug in the engine. Triggers come in two types: external and internal. Habit-forming technologies start by alerting users with external triggers like an email, a link on a web site, or the app icon on a phone. By cycling continuously through successive desire engines, users begin to form internal triggers, which become attached to existing behaviors and emotions. Soon users are internally triggered every time they feel a certain way. The internal trigger becomes part of their routine behavior and the habit is formed.

For example, suppose Barbra, a young lady in Pennsylvania, happens to see a photo in her Facebook newsfeed taken by a family member from a rural part of the State. It’s a lovely photo and since she’s planning a trip there with her brother Johnny, the trigger intrigues her.

Action

After the trigger comes the intended action. Here, companies leverage two pulleys of human behavior – motivation and ability. To increase the odds of a user taking the intended action, the behavior designer makes the action as easy as possible, while simultaneously boosting the user’s motivation. This phase of the desire engine draws upon the art and science of usability design to ensure that the user acts the way the designer intends.

Using the example of Barbra, with a click on the interesting picture in her newsfeed she’s taken to a website she’s never been to before called Pinterest. Once she’s done the intended action (in this case, clicking on the photo), she’s dazzled by what she sees next.

Variable Reward

What separates the desire engine from a plain vanilla feedback loop is the engine’s ability to create wanting in the user. Feedback loops are all around us, but predictable ones don’t create desire. The predictable response of your fridge light turning on when you open the door doesn’t drive you to keep opening it again and again. However, add some variability to the mix—say a different treat magically appears in your fridge every time you open it—and voila, desire is created. You’ll be opening that door like a lab rat in aSkinner box.

Variable schedules of reward are one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users. Research shows that levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect, creating a frenzied hunting state, which suppresses the areas of the brain associated with judgment and reason while activating the parts associated with wanting and desire. Although classic examples include slot machines and lotteries, variable rewards are prevalent in habit-forming technologies as well.

When Barbra lands on Pinterest, not only does she see the image she intended to find, but she’s also served a multitude of other glittering objects. The images are associated with what she’s generally interested in – namely things to see during a trip to rural Pennsylvania – but there are some others that catch her eye also. The exciting juxtaposition of relevant and irrelevant, tantalizing and plain, beautiful and common sets her brain’s dopamine system aflutter with the promise of reward. Now she’s spending more time on the site, hunting for the next wonderful thing to find. Before she knows it, she’s spent 45 minutes scrolling in search of her next hit.

Commitment

The last phase of the desire engine is where the user is asked to do bit of work. This phase has two goals, as far as the behavior engineer is concerned. The first is to increase the odds that the user will make another pass through the desire engine when presented with the next trigger. Second, now that the user’s brain is swimming in dopamine from the anticipation of reward in the previous phase, it’s time to pay some bills. The commitment generally comes in the form of asking the user to give some combination of time, data, effort, social capital or money.

But unlike a sales funnel, which has a set endpoint, the commitment phase isn’t about consumers opening up their wallets and moving on with their day. The commitment implies an action that improves the service for the next go-around. Inviting friends, stating preferences, building virtual assets, and learning to use new features are all commitments that improve the service for the user. These commitments can be leveraged to make the trigger more engaging, the action easier, and the reward more exciting with every pass through the desire engine.

As Barbra enjoys endlessly scrolling the Pinterest cornucopia, she builds a desire to keep the things that delight her. By collecting items, she’ll be giving the site data about her preferences. Soon she will follow, pin, re-pin, and make other commitments, which serve to increase her ties to the site and prime her for future loops through the desire engine.

Super Power

A reader recently wrote to me, “If it can’t be used for evil, it’s not a super power.” He’s right. And under this definition, habit design is indeed a super power. If used for good, habit design can enhance people’s lives with entertaining and even healthful routines. If used for evil, habits can quickly turn into wasteful addictions.

But, like it or not, habit-forming technology is already here. The fact that we have greater access to the web through our various devices also gives companies greater access to us. As companies combine this greater access with the ability to collect and process our data at higher speeds than ever before, we’re faced with a future where everything becomes more addictive. This trinity of access, data, and speed creates new opportunities for habit-forming technologies to hook users. Companies need to know how to harness the power of the desire engine to improve peoples’ lives, while consumers need to understand the mechanics of behavior engineering to protect themselves from manipulation.

What do you think? Desire engines are all around us. Where do you see them manufacturing desire in your life?